Strombolian eruptions

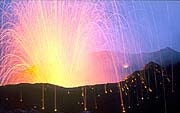

are named from the small volcano-island of Stromboli (image),

located between Sicily and Italy. This volcano has been erupting

almost constantly for hundreds of years. It erupts irregularly

every twenty minutes or so to produce an episodic lightshow that

gives rise to its nickname, the "Lighthouse of the Mediterranean".

Strombolian eruptions

are named from the small volcano-island of Stromboli (image),

located between Sicily and Italy. This volcano has been erupting

almost constantly for hundreds of years. It erupts irregularly

every twenty minutes or so to produce an episodic lightshow that

gives rise to its nickname, the "Lighthouse of the Mediterranean".

The

term "strombolian" has been used indiscriminately to

describe a variety of volcanic eruptions that vary from small

volcanic blasts, to kilometer-high eruptive columns. However,

true strombolian activity is characterized by short-lived, explosive

outbursts of pasty lava ejected a few tens or hundreds of meters

into the air. Unlike Hawaiian eruptions, Strombolian eruptions never develop

a sustained eruption column. They eject relatively viscous basaltic lava from the

throat of the volcano. Build up of the high gas pressures required

to fragment this somewhat pasty lava, results in episodic explosions

with booming blasts. Although Strombolian eruptions are much noisier

than Hawaiian eruptions, they are no more dangerous. As shown

in the images above and below, Strombolian explosions eject bomb- and lapilli-sized fragments that travel

in parabolic ballistic paths before accumulating around the vent

to construct the volcanic edifice. Typically, these eruptions

form scoria

cones

composed of basaltic pryoclasts. However, mafic stratovolcanoes can also exhibit common

Strombolian activity, evident for example, at Mt. Eberus in Antarctica

and at Stromboli itself.

The

term "strombolian" has been used indiscriminately to

describe a variety of volcanic eruptions that vary from small

volcanic blasts, to kilometer-high eruptive columns. However,

true strombolian activity is characterized by short-lived, explosive

outbursts of pasty lava ejected a few tens or hundreds of meters

into the air. Unlike Hawaiian eruptions, Strombolian eruptions never develop

a sustained eruption column. They eject relatively viscous basaltic lava from the

throat of the volcano. Build up of the high gas pressures required

to fragment this somewhat pasty lava, results in episodic explosions

with booming blasts. Although Strombolian eruptions are much noisier

than Hawaiian eruptions, they are no more dangerous. As shown

in the images above and below, Strombolian explosions eject bomb- and lapilli-sized fragments that travel

in parabolic ballistic paths before accumulating around the vent

to construct the volcanic edifice. Typically, these eruptions

form scoria

cones

composed of basaltic pryoclasts. However, mafic stratovolcanoes can also exhibit common

Strombolian activity, evident for example, at Mt. Eberus in Antarctica

and at Stromboli itself.

|

Strombolian activity from Mt. Etna in October 2002. |

Pyroclastic particles like Pele's tears, Pele's hair, and reticulite, which are common in Hawaiian eruptions, are not present in Strombolian eruptions. Spatter-fed flows are minor. Instead, Strombolian eruptions are dominated by scoria fragments, which are highly vesiculated clasts of basalt with a cindery appearance. Tephra bombs and lapilli accumulate around the vent to produce well-bedded, and often well-sorted, scoria-fall deposits

In contrast to Hawaiian eruptions, true Strombolian eruptions produce little or no flowing lava. However, during the end stages of scoria-cone formation, it is not unusual for Strombolian activity to wane and give way to the calm extrusion of basaltic lava flows. As a general rule, a'a lava flows appear to be more common than the more fluid pahoehoe types. As the vesiculating lava is de-gased toward the end of the eruption, it may ooze out from under the volcanic edifice to produce a lava flow, or pond in the vent to produce a lava lake. This will only occur if the underlying basalt is fluid enough to flow, which has not proved to be the case at Stromboli itself.

A classic example of a Strombolian-type eruption was the Paricutin eruption in 1943, about 200 miles west of Mexico City. This eruption marks the first time scientists were able to observe the complete life cycle of a volcano, from birth to extinction.

Three weeks before the Paricutin eruption occurred, the people near Paricutin village heard the rumbling noises that resembled thunder, yet they were confused because the skies were clear of clouds. The noises were associated with earthquakes at depth near Paricutin. On February 20, 1943 a farmer, Dionisio Pulido, and his wife were burning shrubbery in their cornfield when they observed the earth in front of them swell upward and crack to form a fissure 2-2.5 m across. They heard hissing sounds and later described the rise of "smoke" from the fissure, which had the repugnant smell of rotten eggs. The "rotten egg" smell is a hallmark of H2S gas, and the crack that opened in front of them was a fumarole.

|

|

|

|

|

Strombolian pyroclastic activity began at the site the following day and by the end of the day it generated a 40-m-high scoria cone. In one week it grew to a height of 100 m from the accumulation of bombs and lapilli, and it was raining down finer fragments that burned and eventually covered the village of Paricutin. The eruption was unusually long for a strombolian eruption, with several eruptive phases occurring over a 9-year period. After about two years of mostly pyroclastic activity the pyroclastic phase began to wane, and the outpouring of lava from the base of the cone became the dominant mode of eruption over the next 7 years. The eruption ceased in 1952. The final height of the scoria cone was 424 m.